Daniel Mourre, the impossible contemporary

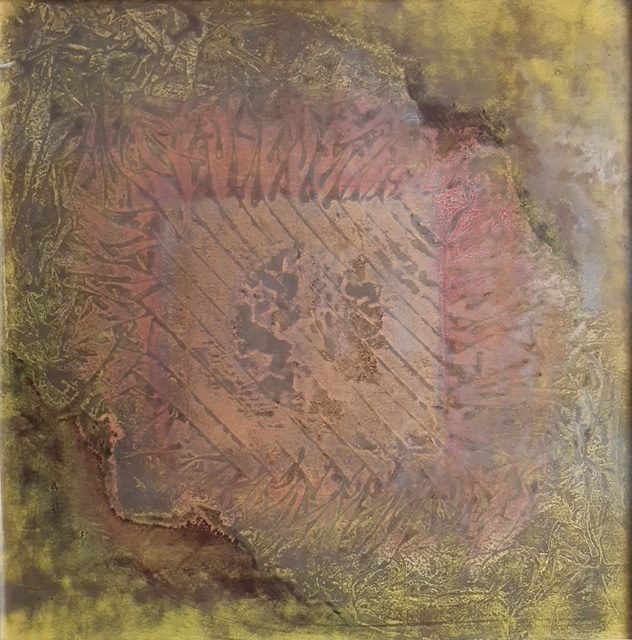

Header Photo Credit: “Recto 1,” iron plate, 100 x 100 cm, 2020, Daniel Mourre. Photo credit: Daniel Mourre Collections.

In one of his many lives, Daniel Mourre used to make mirrors. One would have to write many pages, show a great deal of patience, go back, ask questions, and wonder where his amazing receptiveness came from before being able to summarize its content. It undoubtedly originated within those manifestations that must be classified as marvelous or fantastic phenomena. Obstinately looking for its origins or some proof validating what we have felt would thus be wrong. Confusion does not necessarily mean deception nor chaos. The art of speech does not have to be expressed through language, even less so when it comes to painting. We should believe in the reality of this event despite not quite seeing it with our own eyes. But back to mirrors, let’s remember that Daniel Mourre used to make and exhibit them. He used to dig into resemblance, aiming to underlie tangible things and forms as well as concrete figures with the most vivid brightness, from one corner or contour to another. He is now proceeding in the opposite direction, affirming that while the living image has gone, its imprint remains.

It was during one of his exhibitions that Mourre’s attention was caught by the ground below his feet and that an unexpected strength was revealed to him. Then and there appeared the object that gave birth to the thought process that is now at the center of his life: the manhole cover. It spoke to him and is now the thing around which his entire universe is revolving. After all, one could see in this new body of work a replication of the concepts already found in his former occupation. Whereas mirrors made variations disappear, the artist is now trying to keep track of them. To this end, he uses a material which, although not previously unheard of, has unquestionably become part of his personal signature – rust.

By moving manhole covers from the overlooked horizontality of the ground to the exalted verticalness of the walls, Daniel Mourre creates new cartographies. In so doing, he reminds us of a paleontologist unearthing fossils which , after spending decades underground, are then exhibited in museum display cases.

Photo Credit: Daniel Mourre Collections.

At the origin of Daniel Mourre’s vocation is an impossible concordance with his times: he recovers what gets discarded, hides behind what is usually kept away from view, brings to light what is generally concealed. Working in such a way and negating concepts in such a manner is not leading him to embrace the most current art trends, quite to the contrary; it would rather push him away from those and bring him closer to places not seeking to look pleasant: caves, the underground, and shelters. Wherever he goes he gets strength from. Those cast-iron shields are what protects him best from the indelicacy of time. Practically, the artist uses them as plates that are pressed against canvases, sheets of paper or sheet metal so as to obtain their imprint. He sucks up their skeleton and only keeps their spinal memory. However, he is not the only one to play a part in this pictorial game: inviting their thousand-year-old art of conception to the party, oxidation and chance also have an active role in the end result.

Mourre defends two different techniques, impregnation and propagation. Each one comes with a slew of fables and allegories. Both are means allowing him either to obtain serious effects (the impregnation series) or more animated and vivid ones (the propagation series, where folds and creases resemble an invitation to some party, a joyful and playful celebration). Here more than anywhere else, the presence of the manhole cover is not obvious: it seems to give way and bow to a flurry of vegetal elements and is therefore not immediately distinguishable. Thus, the artist seems to allude to the triumph of nature after man’s disappearance, a way for him to strengthen the pro-environment discourse that lies behind his work without fully expressing it.

In the same way, he collects imprints of curled up or lying bodies or those of clothes that are sometimes perfectly recognizable and at times half erased. All of this is part of the continuity of a body of work disrupted by archaeological desires. Pieces of legs and a great number of armless hands placed on various surfaces can be seen. A thinker in a fetal position, reminiscent to that of Rodin, can be distinguished in a headless and muscular block, as well as tank tops, T-shirts, overalls, shorts, and even a bedsheet resembling a burial shroud. When considered separately, all of these things are tragic. There are of course funereal undertones to Daniel Mourre’s work; he is not the kind of man who paints to relax. The artist considers painting seriously in order to better reveal the titanic truth that it is the repository of. One cannot help but think of some nuclear catastrophe petrifying everything in its wake. Just as the Hiroshima bomb etched the silhouettes of men and objects on house walls, the imprints that Daniel Mourre creates with his chemical solutions make the viewer wonder whether some disaster could have been at work here. One cannot imagine that this was born without pain, or that it could be replicated for pleasure.

While these compositions have an undeniable dark beauty, the sun still makes an appearance here and there. One look at the “Empreintes sur tôle” series is enough to be immediately convinced that no disaster could have produced such bright colors seeming so happy to manifest their presence, their joy of being. In what can be seen as a happy contradiction or a lovely paradox, the manhole cover turns solar. Light does no longer come from the sky – brightness springs from the ground. Singularity is at work, made of yellow mixed with lilac, of greenish blue, of red clashing with gray, of orangish fighting with brown. “Bicephalous”: that is how the artist wittily refers to those double-sided works. Thus, the same work can have completely different moods depending on which side is presented to the viewer.

While one might think that Daniel Mourre’s work combines the dawn and the twilight of our civilization, it would be wiser to say that he considers civilization from its dawn to its twilight, which is not quite the same. In his work, the ancestral, ancient gesture meets the end of times, forecasting a society that would have fallen into chaos. Only devastation would remain after such an industrial disaster. That way, the artist’s speech serves as his mission statement; he leans on his vision as he would on a fiction used to formulate (or predict?) the fall of humanity. He imagines this survival situation by arguing that Man would need to find refuge in sewers and the underground. Yet his art is no parallel to what can be found in works of science fiction. His photograms don’t just show remains: they freeze moments of earthly beauty, sumptuous coronations obtained by the humble elements on which we walk.

From now on, one thing is certain: we will never look at manhole covers the same way.

www.danielmourre.com

Fantastic read! This article does an excellent job of breaking down what smart homes are and how they’re transforming modern…