The Donut Dollies: A Brief History

A few weeks ago, my wife and I packed our bags and moved to a new house. Prior to our departure from Commerce, we stopped by our favorite doughnut store in the area—Kim’s Donuts. As we enjoyed the scrumptious sugared pastries, we shared a laugh and recollected the fond memories we had both made in Northeast Texas. Too much astonishment, I recently found out that the doughnut was not intended to be a treat for a commoner like myself. Hansen Gregory, a Massachusetts sea captain, created the first doughnut in 1847 (the lumps of fried dough were also known as ‘oily-cakes’). Doughnuts, like every other pastry in the United States during the nineteenth century, were reserved for and eaten only by the wealthy. It was not until the world wars of the twentieth century when doughnuts were made readily available for the general public. In this article, I intend to shed light on the Donut Dollies, young women who played an instrumental role in providing encouragement and fresh doughnuts to soldiers and French villagers overseas, yet sadly remain a footnote in current history books.

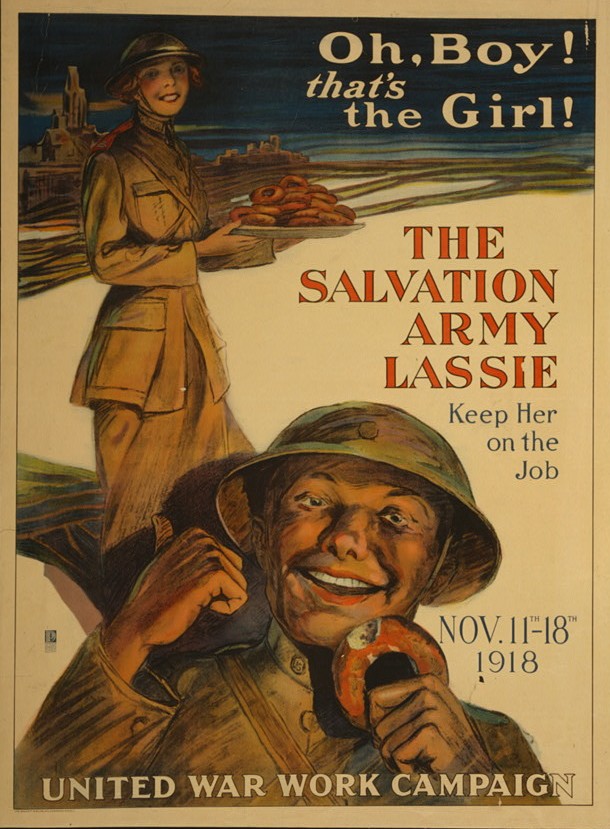

When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, the Salvation Army, a recognizable Christian organization, recruited 250 woman volunteers whose primary function was to assist the soldiers and bring a piece of normalcy to the American front. One of these recruits was Helen Gay Purviance, a Rochester scholar who took her role seriously, serving hot chocolate and clean black socks, piling ammunition trucks, giving spiritual advice, and playing surrogates for wives and mothers (volunteer Barbara Pathe recalled being asked by a 19-year-old private to hear his stories of home and family, and later commented that, “Listening was the biggest thing we did…”). Although the women were required to travel with soldiers, the Army generals were not so keen on having females at the front lines. In a letter to a close friend, Purviance details the officers’ disapproval: “General [John J.] Pershing wasn’t keen about women going close to the front lines. He said he didn’t want to take responsibility for us. We told him he wasn’t. We were taking responsibility to do this.” The young women, intent on providing the soldiers a morsel of support and encouragement in the face of danger, were far from helpless—each was outfitted with a gas mask, helmet, and .45 caliber revolver (they had been trained on firing the weapon). As the months dragged on with no peace treaty in sight, Purviance and her associate Margaret Sheldon became disgusted at a non-appetizing, gooey concoction called ‘bully beef soup’ that the cooks served the soldiers. They wanted to serve luscious confections that would remind the tired, homesick men of their mothers’ kitchens. The pair initially created cookies, and using excess cookie dough, planned to bake old-fashioned American pies.

Since fruits were in short supply and the horrific conditions in the trenches made baking near-impossible, the young women dismissed their previous pie idea and instead, using empty wine bottles for rolling pins and soldier’s helmets filled with lard, created fried little pastry dumplings called doughnuts. The “puffy mounds of fried deliciousness”- which required a small amount of basic ingredients, including flour, sugar, baking powder, salt, eggs, milk, and powdered sugar – gave the American soldiers a warm lump of home, something that was desperately needed in the muddy, rat-infested, and rather uncomfortable trenches. In a letter addressed to her family in Huntington, Indiana, Purviance wrote that in spite of the back-breaking work to make a very small batch of doughnuts, it was worthwhile to bake “some good American food” and bring a smile to the soldiers’ grim faces: “I was literally on my knees when the first doughnuts were fried, seven at a time in a small frypan. There was also a prayer in my heart that somehow this home touch would do more for those who ate the doughnuts than satisfy a physical hunger.” Soon, the tempting aroma of frying doughnuts spread throughout the trenches and lured the soldiers to the crude hut where Purviance was making the delectable goodies. A line of soldiers patiently waited for their sugary bite in the sludge and rain. The first doughnuts were “much smaller than modern ones,” according to historian Patri O’Gan, yet were received by the U.S. soldiers with much enthusiasm, nonetheless. Private Braxton Zuber secured the first treat and after licking the sugar off his lips, he reportedly exclaimed, “If this is war, let it continue!”

in the French trenches, 1918

after the D-Day Invasions, 1944

Purviance (and later assisted by Sheldon) only made 150 hand-made doughnuts on the first day owing to the absence of conventional kitchen equipment. The young woman pledged to review her cooking strategies to ensure she met the soldiers’ profuse demand for doughnuts. When one soldier requested a sugary doughnut with a hole in it, Purviance did not hesitate in creating a new recipe to satisfy the soldier’s craving. She went to a blacksmith and asked if he could fuse an empty condensed milk can and a shaving cream canister to produce the now-iconic circular mold (this procedure took longer than anticipated because neither Purviance nor the local forger spoke each other’s languages so many visual gestures were used). The circular treats with a hole in the center were quickly devoured by not only American soldiers, but also the French public. As a token of appreciation, Purviance and the “Doughnut Girls” gifted a bag of delicious, holed doughnuts to the blacksmith and neighboring villagers. Recipes and praise for these tasty treats quickly spread to surrounding towns, where many began baking the holed doughnuts in their kitchens and passing over the previously-desired beignet, a Louisiana-styled pastry that was deep-fried and coated in a thick layer of powdered sugar. By the end of World War I in November 1918, France had hungrily adopted the mouthwatering, circular sweet tidbit from America known as the doughnut.

circular doughnut mold, 1917

Despite the Great Depression in the 1930s, where Europe and the United States experienced a significant rise in bank failings, unemployment, and food shortages, the French did not have to wait for long until another bloody world war prompted the return of American women serving many platters of doughnuts. During World War II, the Red Cross picked up the treat mantle and restructured the Doughnut Girls. The organization, now labeled “Donut Dollies”, activity sought female recruits who were between 25-35 years old and matched specific requirements, which included some college education and work experience, stellar reference letters, as well as “be healthy, physically hardy, sociable and attractive.” Owing to this rigorous selection process, 1 in 6 recruits made the program. The newly-picked Donut Dollies received multiple vaccinations, were outfitted in neat Red Cross uniforms, and engaged in basic training on the history as well as policies and procedures of the Red Cross. The training occurred at the American University in Washington D.C. with considerable attention on how to properly represent the United States on the world stage (which involved constantly smiling and wearing no earrings nor excessive use of cosmetics). Since President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration noted that maintaining troop morale in desperate conditions was a major component of victory, the Dollies were asked to also provide emotional support. Many Dollies learned French and read books on European culture prior to their shipment. Over 300 Dollies were transported to Europe in early 1944.

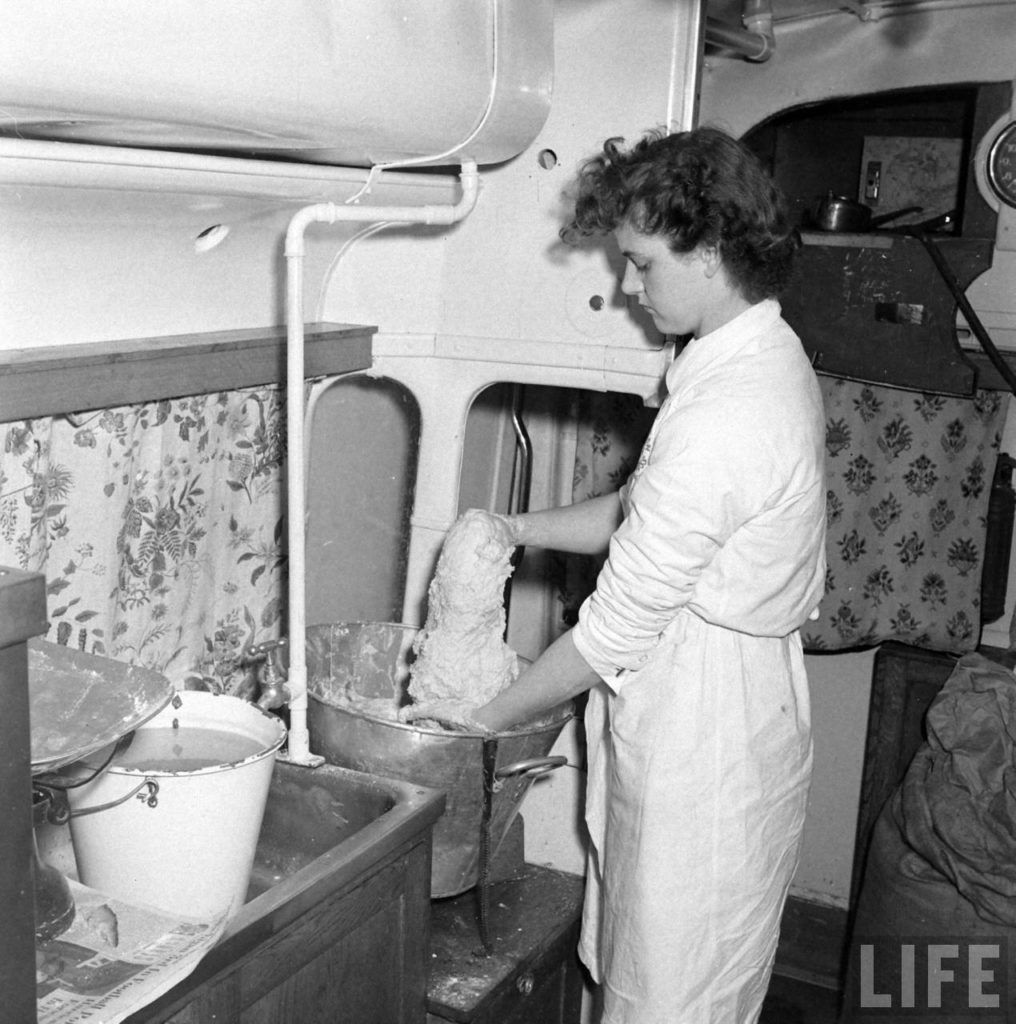

In preparation for the Normandy landings in June of 1944, the Red Cross outfitted 100 English Army buses with full kitchens and donut-machines provided by the American Donut Company (the donut-machine, complete with a powerful and heavy whisk, had been invented by Adolph Levitt, an enterprising refugee from Russia, in 1920). Nicknamed ‘club-mobiles,’ these vehicles were also equipped with sleeping bunks and a cozy lounge area. Three Dollies were assigned to each truck, in addition to one British police officer, who would drive the club-mobile. Once the club-mobile had parked in camp, the Donut Dollies would immediately start creating and baking doughnuts for hundreds of hungry soldiers—the cooking was strenuous and often took several hours. Clara Schannep Jensen, a Dolly from the Midwest, wrote about her experience in a 1944 letter: “The day before yesterday we spent the whole day making doughnuts. They were pretty good, too!” Once the piping-hot doughnuts were ready to be served, the Dollies played sweet classical tunes on their trucks’ speakers via a timely record player, announcing the start of the soldiers’ supper. Doughnuts were served with coffee. The music enticed much dancing among the soldiers, who obviously missed the wild dance halls back home. Since the War Department decreed that the Red Cross would be the only civilian service group allowed overseas to assist the U.S. Army, the Donut Dollies not only provided sweet treats, but also books, newspapers, candy, gum, cigarettes, and good ‘ole company.

After the highly-successful, yet bloody D-Day beach invasions and liberation of Paris, 8 club-mobiles followed the U.S. Army through Luxembourg, Belgium and Germany. This small group included four young Dollies from Texas who proudly painted the flag of the Lone Star State on the side of their truck—Dorothy Boschen, Virginia Spetz, Jane Cook, and Meredyth Gardiner (the quartet stayed together despite the three-Dollies-to-one truck-policy). They provided warm sweets and hearty conversations to the 36th Infantry Division, a tough unit comprised of Texas and Oklahoma National Guard soldiers. Along with their laborious baking duties, the Texas gals thoroughly enjoyed chatting with the inquisitive locals, giving French school children sugared treats and answering questions the villagers had regarding culture and music in America. The Dollies continued their baking services and supplying voluntary aid to the Army’s wounded and sick until the end of World War II in August of 1945. The Dollies’ tireless efforts in feeding and providing solace for the shell-shocked men (and sporting big smiles) were greatly appreciated—in one of his letters published by the Boston Daily Globe at the war’s conclusion, Sergeant Edgar S. Chase noted his favorite part of the front: “Can you imagine hot doughnuts, coffee and pie and all that sort of stuff? Served by mighty good looking girls, too.” It is now estimated that the Red Cross Donut Dollies served 4,659,000 doughnuts to soldiers during the Second World War (and this does not include the number of toothsome pastries they gave to French citizens!). When the soldiers returned home, they quickly spread the news of their favorite treat.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress online collections.

The Donut Dollies continued to circulate their cheeriness and aromatic treats to American military camps in Vietnam and Korea during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Furthermore, they encouraged communities at home to celebrate National Donut Day, a June holiday that was originally created by Chicago’s Salvation Army as a fundraiser during the Great Depression. As a consequence of their charitable efforts, the doughy and sugary pastry that we famously call the doughnut was made available to many French and American households—the doughnut, consumed by the masses, became a symbol of home, love, and liberty. Today, according to countless food and nutrition statistics, 10 billion doughnuts are sold in American stores every year. We could sit back and debate the merits of Dunkin’ Donuts v. Krispy Kreme, but one thing we can all agree on is that Americans loves their doughnuts… the average American eats a staggering 31 doughnuts each year. In France, the doughnut is not quite as popular as a fresh baked croissant, yet the circular treat is on display in many restaurants, supermarkets, and bakeries (and is usually devoured by hungry teenagers on the way to school). The Donut Dollies, angels among chaos, introduced delicious doughnuts when they gave up the safety and comfort of their homes to fly thousands of miles to simply put a bright smile on a soldier’s face or give him a few minutes of peace and blissful heaven in a crazy, dangerous world.

Bibliography

Airy, Helen. Doughnut Dollies: American Red Cross Girls During World War II, A Novel. Santa Fe, NM: Sunstone Press, 2016.

Healey, Jane. The Beantown Girls. Seattle, WA: Lake Union Publishing, 2019.

McBride, Connor. “Helen G. Purviance: The First Salvation Army ‘Doughnut Girl’.” World War I 100 Years. Last modified in November 2017. https://www.worldwar1centennial.org/index.php/indiana-in-wwi-stories/2433-helen-purviance.html.

Mullins, Paul R. Glazed America: A History of the Doughnut. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 2008.

Header Credit Photo: Library of Congress online collections.

Hi Mr. Chanin